Co-authored by Cohere, Global Schools Forum, Ki4Bli (Kenya) and YIDA (Uganda)

Early childhood is a critical window for shaping lifelong outcomes in learning, health, and wellbeing. Research shows that high-quality, birth- to-five early childhood programs for disadvantaged children, yields a 13% return on investment per child, per annum through better education, economic, health, and social outcomes. But for children living through displacement, this window is often compromised by fragmented systems, under-resourced programs, and a lack of continuity in care and education. Only 38% of refugee children are enrolled in pre-primary education- compared to a global average of 61%-a stark gap during the most foundational years.

In these settings, refugee-led organisations (RLOs) play a critical but under-recognised role. Evidence highlights that RLOs are more likely to lead responses that are accountable, legitimate, transparent, effective and impactful. They are also best placed to articulate the needs of their communities and influence policy from above. Yet RLOs continue to operate on the margins of formal humanitarian systems. The Grand Bargain’s 2016 commitment to channel 25% of humanitarian funding to local actors by 2020 remains far from reach—with only 1.2% of funding allocated to local actors in 2023, with refugee-led groups receiving even less.

In this blog, on World Refugee Day, we recognise and celebrate refugee leadership as central to shaping effective, equitable early childhood systems in crisis-affected settings and outline ways in how global actors can work in true partnership to help with scaling and sustaining their impact.

What makes refugee-led early years work unique

While global discourse debates how to localize humanitarian response, RLOs are already demonstrating what works. Two organisations- Youth Initiative for Development in Africa (YIDA) in Uganda and Kalobeyei for Better Lives Initiative (Ki4Bli) in Kenya – offer compelling proof of concept for effective, community-rooted early childhood systems in displacement settings.

Uganda hosts more than 1.8 million refugees—the largest number in Africa—under a progressive refugee policy that allows for freedom of movement, the right to work, and access to public services. Yet despite these commitments, early childhood education in refugee settlements remains severely under-resourced. The government provides only regulatory oversight, with service delivery largely left to private actors and non-state providers.

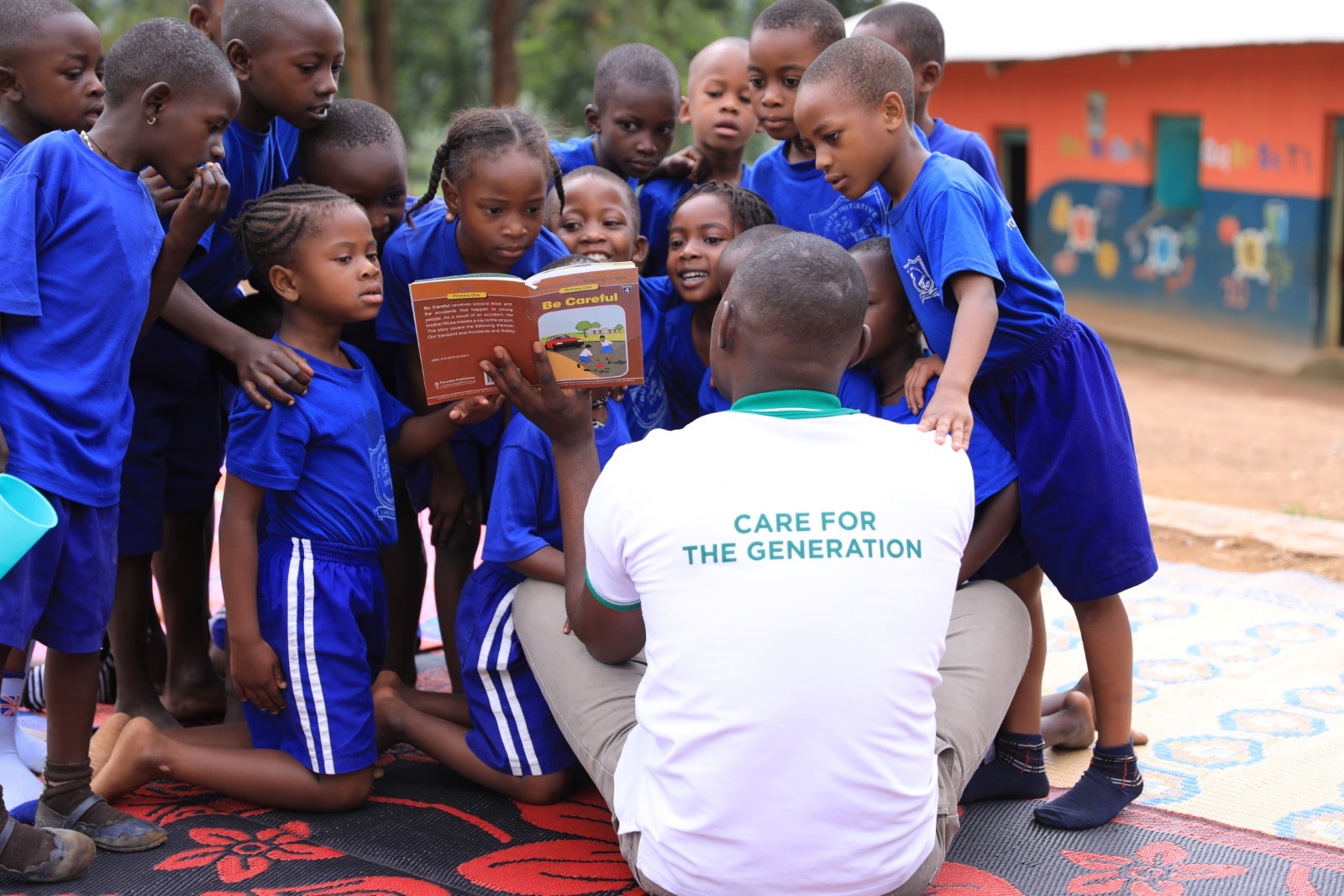

In Kyaka II settlement in Uganda YIDA runs structured early childhood programmes for children aged 3–8, led by trained refugee youth. Grounded in community realities, YIDA is uniquely positioned to address challenges that often arise in displacement settings—such as language barriers, staff retention, and cultural disconnects —where external actors often face limitations. For example, many young children speak Kiswahili or French in Kyaka II settlement, but are expected to learn in English. YIDA’s language-sensitive approach ensures that learning remains accessible and meaningful. Their classrooms are also open to both refugee and host community children – a deliberate choice that fosters inclusion, reduces tensions, and builds mutual understanding across communities who share the same limited resources. They have also started initiatives like school farming which help ensure consistent access to food in resource-constrained environments and linkages to school feeding or income generation of families recognising the economic pressures families face in these contexts. Lastly, they also train refugee youth as teachers helping build a sustainable pipeline of local leadership.

Kenya is home to over 700,000 refugees, many of whom reside in complex, semi-integrated settlements like Kalobeyei. Here, the Kalobeyei for Better Lives Initiative (Ki4Bli) operates in a restrictive policy environment where refugees face limitations on land ownership, formal infrastructure, and legal recognition. Despite these structural constraints, Ki4Bli runs Light Academy – nan accredited school serving 300 children across primary and secondary levels. As a refugee-led organisation, Ki4Bli does not treat education as a standalone service, but as part of a broader strategy for community wellbeing and future readiness. Ki4Bli has built a three-pronged model: delivering the national curriculum to ensure formal progression; embedding digital and socio-emotional learning to equip children for a changing world; and empowering parents as co-managers of the school and participants in livelihood activities.

Both organisations succeed where traditional approaches struggle. Led by individuals with lived experience of displacement, they design culturally relevant programmes that make learning meaningful and accessible. Their deep trust within communities also strengthens program sustainability. RLOs are also uniquely able to innovate under resource constraints – designing practical, low-cost solutions that have the real potential to scale.

Barriers RLOs face

RLOs like YIDA and Ki4Bli hold key strengths yet they face barriers that hold them back. Key barriers are:

- Funding through intermediaries: RLOs are rarely funded directly and resources flow through intermediaries. Without core funding, RLOs have to depend on temporary and restrictive funding streams that make it difficult to invest in essential infrastructure – such as classrooms, feeding programmes, teachers, or learning materials – or to scale their services.

They are frequently perceived as “high risk” by donors due to a combination of factors – such as lack of formal legal status, limited financial reporting systems, absence from official registries, or small operating budgets. These characteristics often stem from the structural limitations of operating in displacement contexts, rather than from poor performance or weak capacity.

What’s needed are funding and assessment approaches that recognise RLOs’ strengths – particularly their deep community trust, proximity, existing capacity and adaptability – and that support them with direct, long-term investment in institutional capacity.

- Exclusion from decision-making spaces: Despite delivering essential services, RLOs are typically confined to implementation roles, with little influence over how systems are designed or how resources are allocated. They remain largely absent from coordination meetings, technical working groups, and sector planning forums where critical decisions are made.

This disconnect results in policies shaped without the insights of those who understand the context best – leading to solutions that often fail to reflect community needs or realities. RLOs must be recognised not merely as service providers, but as essential strategic partners. This requires creating space for their meaningful participation in decision-making processes at every level.

- Fragile operational models due to legal and policy constraints: Across many contexts, RLOs face structural barriers that limit their ability to operate, expand, or formalise their work. Host country policies often restrict refugee-led groups from registering as legal entities, owning land, or accessing public systems – treating them as temporary actors rather than long-term partners.

Without legal status, RLOs cannot establish secure partnerships with government agencies, international donors, or private sector actors. They remain excluded from formal financing mechanisms and are unable to make the long-term investments necessary for sustainable program expansion. Most critically, these barriers prevent RLOs from integrating their expertise and community connections into national education systems, where their impact could be transformational. Unlocking their potential will require policy shifts that recognise RLOs as legitimate stakeholders in education delivery and system-building.

A call for deeper partnership with RLOs – from donors, INGOs, and governments

Refugee-led organisations have shown what’s possible when those closest to the challenge lead the response. What’s needed now is a shift in how systems recognise and enable this leadership – through direct funding, legal recognition, meaningful policy inclusion, and long-term capacity support. With the right conditions, RLOs can move from sustaining services to scaling solutions.

The opportunity ahead is one of shared leadership. Donors, INGOs, and governments each have a role – not only in resourcing refugee-led efforts, but in shaping systems where RLOs are central partners in early childhood development. We invite you to reflect:

- As a donor: What would it take to shift from funding through intermediaries to resourcing RLOs directly? How might you build funding relationships rooted in trust, not just compliance?

- As an INGO or implementing partner: How can your organisation cede space, share power, and act as an ally rather than a gatekeeper?

- As a policymaker or education system leader: What needs to shift across policy, regulation, or financing to formally recognise refugee-led organisations so they can register, scale, and partner in shaping inclusive education systems over the long term?

Leave a Reply