With aid cuts, worsening climate crises, conflict and wars across the globe, it is fair to wonder; why bother with language at all? Isn’t it a distraction from the real work? A change in vocabulary will not save lives or dismantle systems of oppression on its own; and too often, language reform becomes a cosmetic gesture, signaling progress without actually redistributing power. Swapping “beneficiary” for “community member” means little if decisions remain concentrated in Geneva, London, or New York. Critics of “language policing” rightly warn against hollow word-swaps and performative progressivism. In a sector where resources are shrinking and the stakes are high, focusing on terminology can seem like the privilege of well-intentioned insiders even sidelining more urgent initiatives.

I hold that tension too. I’ve questioned whether focusing on language is even my place, or if it is a distraction from avoiding the harder task of changing the sector. But again and again, I return to this: language is a mirror and a tool. It shapes how we relate to one another, whose knowledge we value, and how we perceive power. Ignoring language risks reinforcing the very hierarchies we claim to dismantle. This blog is not about semantics for their own sake; it is about recognising the deeper truths our words either obscure or illuminate, and why aligning how we speak with what we believe still matters.

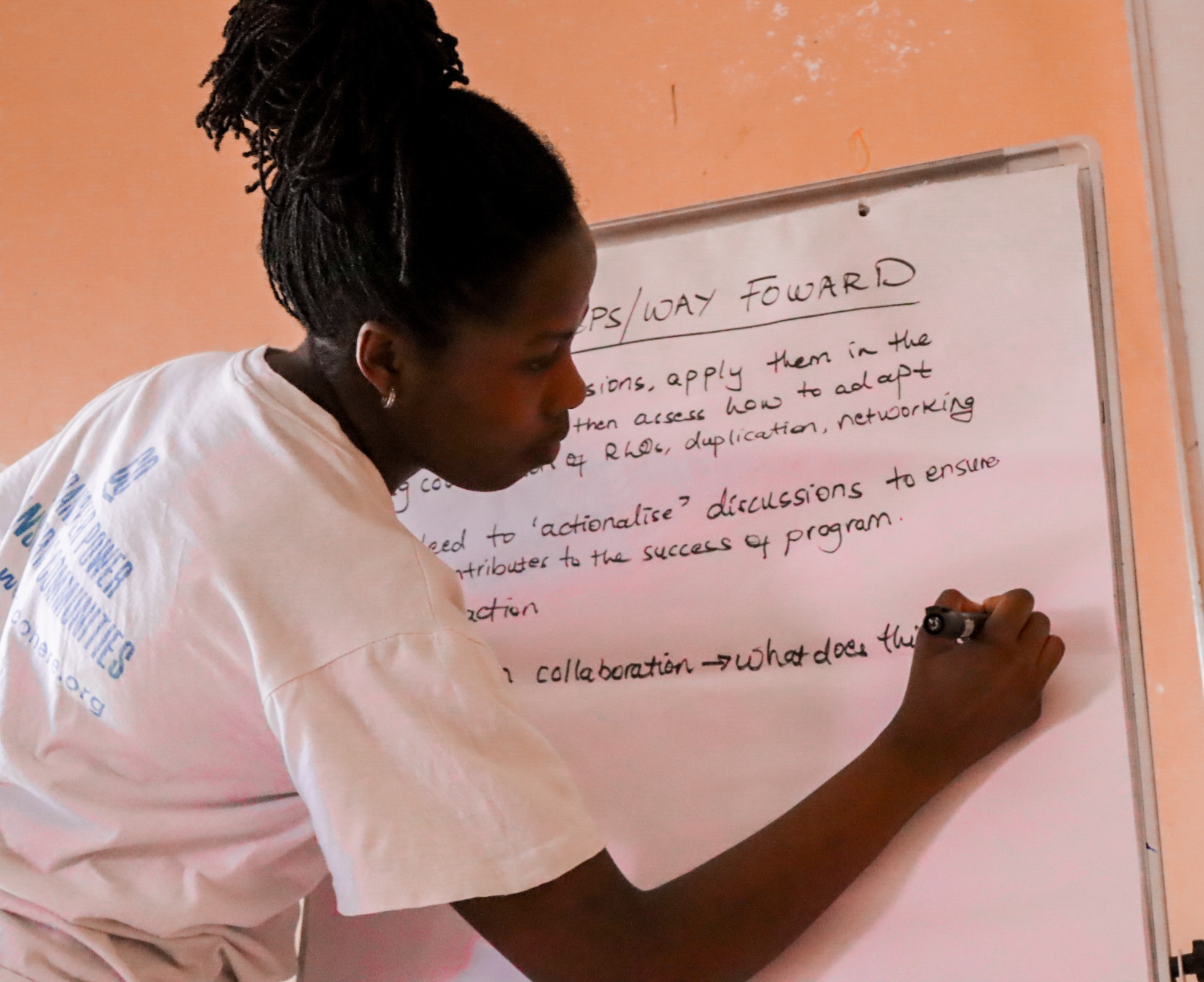

There are certain phrases we use in the humanitarian aid sector without thinking. For instance, words like “on the ground,” “beneficiaries,” “capacity building,” or strings of acronyms like RLO, CBO, INGO. We have inherited this language from a professional culture shaped by funding cycles, reporting frameworks, and technical disciplines. They are familiar and we may console ourselves by saying ‘everyone is using those words’, but that’s exactly why we need to assess our role in conforming to the norm by pausing, questioning, and truly listening.

Recently, I came across someone describing the term “on the ground” as problematic. I’ll admit, I brushed it off at first. It seemed like over-policing language. But over time, I’ve found myself pausing more often and thinking:

- What am I really saying when I use this phrase?

- Whose perspective does it center on?

- And who might it be excluding?

I’ve used this phrase countless times, without malice, and often without much thought. It seemed like harmless shorthand to refer to people or organisations doing work in communities, often in forced displacement settings. But as I’ve listened more deeply to peers and partners, especially those with lived experience of forced displacement, I’ve started to hear what’s underneath the phrase.

Who is “on the ground”?

Even if we might not admit it, when we say “on the ground,” what are we implying? That someone else is above? That people doing work in their own communities are somehow different from “us”, the intermediaries, donors, planners, strategists, or international staff?

I have come to realise the phrase quietly reinforces a hierarchy of distance: a view from above, looking down. It turns lived realities into locations to be monitored, visited, or reported on, rather than acknowledged as the center of knowledge and decision-making. And often, it reflects the point of view of someone not “on the ground”, someone observing from a distance.

Language does more than describe, it shapes how we allocate resources, whose voices we prioritise, and whose knowledge we consider legitimate. When we use phrases like “field staff,” “implementers,” or “local actors,” we risk unintentionally defining people by their proximity to power, or lack thereof.

And then there’s the jargon and acronyms that turn people into policy terms, or euphemisms that blur accountability. Terms like IDPs (Internally Displaced Persons), RLOs (Refugee-Led Organisations), FBOs (Faith-Based Organisations), or PSEA (Protection from Sexual Exploitation and Abuse) and etc are useful for shorthand, but they also risk reducing people and lived experiences to technical categories.

Euphemisms like “Lessons learned” can sometimes replace actual accountability, implying reflection without change. “Capacity building” subtly assumes that communities lack capacity, instead of recognising already existing knowledge.

Take the word “empowerment.” It sounds positive, even harmless, but it quietly reinforces a troubling idea: that power is something we give to others, rather than something they already hold. When we say we’re “empowering people or communities,” we often center ourselves as the actors, overlooking the leadership and knowledge that already exists. Using that kind of language can make it seem like we’re helping, while actually covering up the real, deeper issues, like unfair systems or power imbalances, that we haven’t addressed or changed.

We can’t build inclusive systems using exclusionary language.

Are We Over-Policing Words?

Of course, there’s a risk on the other side too. Language evolves, and not everyone who says “on the ground” for example, is reinforcing colonial power structures. There’s a danger of shaming people for not using the “right” terms, or for speaking in ways that are familiar to them. Policing language without building shared understanding can alienate, not transform.

A recent conversation made me pause and reflect on this tension more deeply. Someone asked me, quite genuinely, what legitimacy do I have to question what people say in everyday interactions, or to dictate how they should be using certain terms? I caught myself feeling triggered. At first, I wanted to defend my position, to explain that language matters, that words shape power. But the question stayed with me.

It forced me to confront my own discomfort. Was I approaching this from a place of care or from a place of control? Was I inviting reflection, or unintentionally imposing a standard? The truth is, I don’t want to dictate, I want to invite dialogue. But I also don’t want to pretend language is neutral, or that I should stay silent to avoid discomfort.

I’m learning that it’s not about having legitimacy as much as it is about taking responsibility. Not to police, but to participate.

So the goal isn’t to make people feel bad for the words they use. It’s to encourage awareness: Why do we use the language we use? Who does it serve? Who might it exclude?

What We Can Do Instead

We can start by being specific. For example, instead of “people on the ground,” we can name who we’re talking about: refugee-led organisations, community leaders, women’s groups in northern Uganda, or just simply our partners. We can speak from a place of proximity rather than distance, describing what people are doing, not where they stand.

We can also invite others into our language. Rather than hiding behind acronyms or jargon, we can explain things in accessible terms.

And we can remain humble. Words will change. What feels thoughtful today may feel outdated in two years. What matters is our willingness to listen, learn, and evolve.

In the End, It’s About Inclusion

Whatever the context may be, the words we choose should reflect the relationships we want to build with our partners: inclusive, respectful, equitable and grounded in mutual trust.

So no, I’m not suggesting we create a blacklist of forbidden words. But I do think we should pay attention. Because language isn’t neutral, it either builds bridges or reinforces walls.

In the end, it’s not just about the words themselves, it’s about what they signal, what they open up, and what they shut down. Language will always evolve, but if we let it, it can evolve toward connection rather than control.

Leave a Reply